NEVER CURSED is a bi-monthly newsletter about movies I love & the people who make them.

Over the various world crises, strikes, and “industry contractions” of the past year, it’s been a challenge to remember why filmmaking is personally and politically important to me. I’ve started this column to revisit both old favorites and new wells of inspiration (more on that next week!). I hope you’ll join me.

This Week: NEVER CURSED’s first issue is about the romance of the rewatch, my favorite film to revisit, and the inspiration for this column’s name: Phantom Thread.

Phantom Thread is, in many ways, the perfect Valentine’s Day rewatch. I find it to be hopelessly romantic, delivering the kind of twisted love story that every obsessive artist secretly hopes for – patience, understanding, collaboration, and a much-needed (if traumatically-enforced) day off. I watch this movie a few times a year, and no matter what I’m searching for – New Year’s Day hangover cure, writers-block-breaking inspiration, palette reference for a manic apartment painting project, etc. – it never fails to unveil new secrets. It’s an incredibly generous movie in this way, always receptive to whatever new patina my current mood or focus lends it.

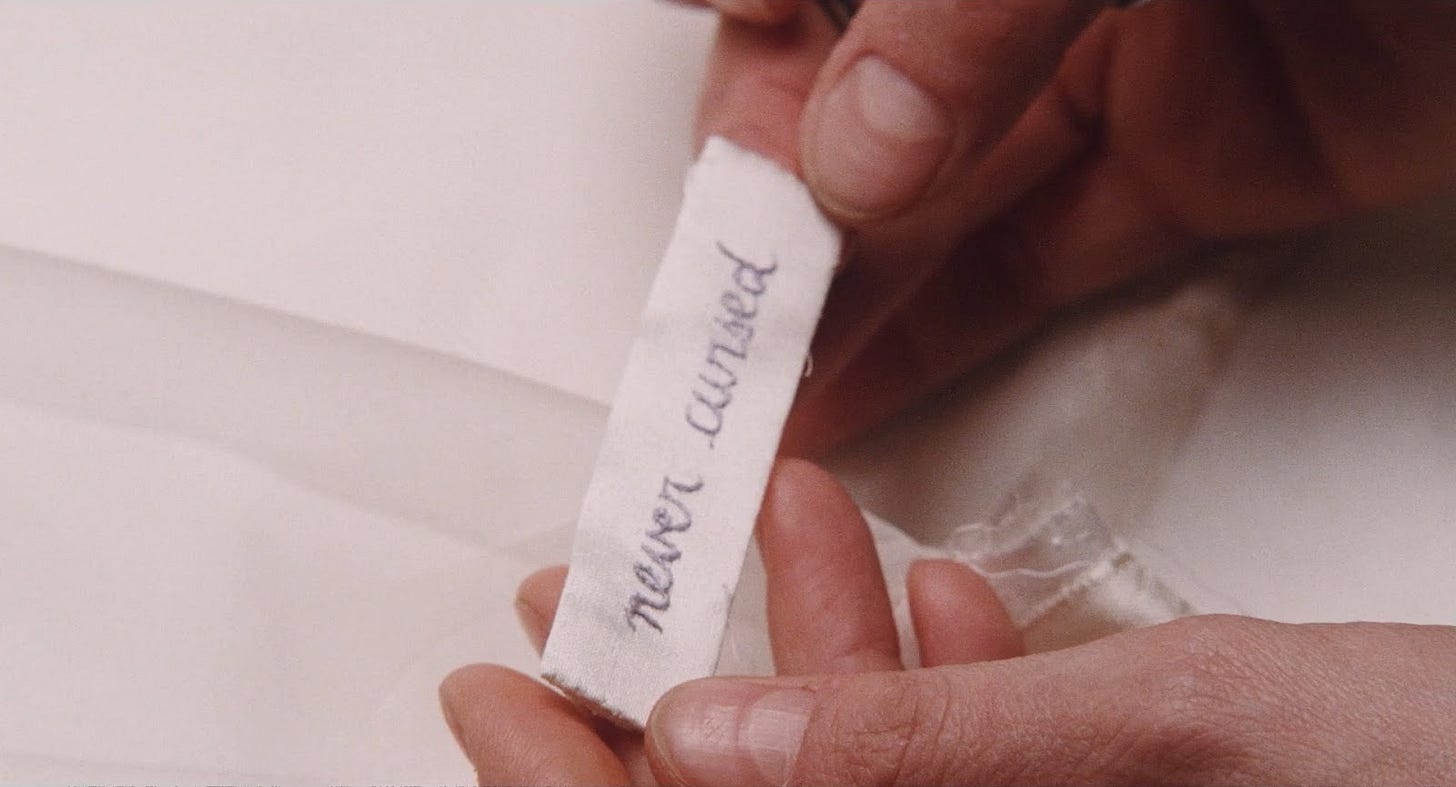

I love Phantom Thread for many reasons: its visual craftsmanship, its memorable dialogue, its knotty and subversive depiction of heterosexuality. But most of all, I love Phantom Thread because the House of Woodcock feels so close to a film set, bustling with craftspeople under the direction of an artist who trusts them enough to stitch his secrets into the work passing through their hands. Watching and rewatching it, I wonder if Anderson and his collaborators, like Woodcock, have hidden memories and mementos of the people they love in the lining of this film: a line here, a specific prop there. This column is named after Woodcock’s stitched prayer – “never cursed” – because the kinds of movies I love are ones that pulse with these hidden personal details. Nothing could be more romantic to me.

I am and have always been a compulsive rewatcher. Most of us grow out of the habit of grinding a film into the dust when we stop watching, say, Bambi, but the films I really love are the ones who welcome me back, time and time again. Phantom Thread is at the top of that list — I saw it multiple times in theaters when it first came out, and make a habit of returning to it every few months, whether in retrospective screenings or at home on my laptop. Its structure is deceptively straightforward: a meet-cute leads to a romance, which leads to alienation, which resolves in reconciliation. But Phantom Thread pulls from so many references and is so meticulously constructed that I discover something new in it every time I watch.

The first time I saw Phantom Thread, I thrilled at PTA’s early feint that the Woodcock siblings (played, of course, by DDL and Lesley Manville) might be in some sort of illicit, incestuous relationship. As a lover of Rebecca, any sort of Mrs.-Danvers-coded character is going to immediately pull my focus. But while Cyril’s knowledge of Reynolds’ preferences in women felt territorial on first viewing, it now feel like the dispassionate observation of a woman whose business and peaceable breakfast consumption depend on an understanding of her brother’s whims. After taking up with Reynolds, Alma (Vicky Krieps, queen of my heart) soon finds herself uneasily in the middle of an entrenched family dynamic, in the same way anyone does when they first see a partner in the context of their parents or old friends. We (and Cyril) know well before Alma does that the windswept, carefree man she met at the roadside cafe requires a hearty scaffolding of routine and emotional support in order to function.

The life of a Great Man’s wife, Reynolds and co. seem to assume, is one of sacrifice and submission. But becoming his real partner, perhaps, requires something else. The occultist novelist Charles Williams, a comrade of Tolkein and Lewis, once wrote to his mistress, Phyllis Jones: “I love you baby, I love you defiant witch!” Phyllis was an enthusiastic but rebellious participant in his sado-masochistic fantasies; a private world that bled into his novels and academic lectures, but did not seem to permeate his marriage with Florence, a schoolteacher. Woodcock seems to think of his needs as being in line with other Great Men like Williams, his great output enabled by absolute control in the home.

Maybe that was once true. But a couple viewings in, I realized that Alma is encountering Reynolds past his prime, rakish charm dulled by the sense of looming obsolescence and death. She alone understands the prayer Reynolds stitches into the seams of every garment in his atelier: to avoid the dressmaker’s lonely curse, to relinquish authority and still find love on the other side. Alma’s power over him is “like a fog as it rolls in,” as PTA described it. Even Williams, whose proclivities were definitely more sadist and controlling than otherwise, revered and required rebellion from his lover, Phyllis. Unlike the crybaby men that proliferated in movies in the last year, protesting the injustices of assorted alpha femmes, Reynolds finds himself eager for the absolute release of being dommed by his “defiant witch,” who soon becomes his wife.

The last time I saw Phantom Thread in a theater, it was New Year's Day and I was sitting next to my first real Valentine, someone I still love very much, though in a different way than when we first met. In the dark next to them, quietly recovering from our festive hangovers, I realized that true companionship feels like rewatching a favorite film: the heady infatuation of a first encounter changing over time to a deeper sort of understanding; the reflexive laugh at a joke you've heard a thousand times before; the comfort of knowing (generally) what scene or mood comes next; and -- most precious -- the joy of still being surprised when you notice, so many years in, a new detail that was there all along.

I know this movie well enough by now that I can let my mind wander while I watch it, catching on a different thread each time, brushing past the phantom hands of everyone who constructed it. The familiar score swells, and I settle in, gladly submitting to Alma’s story for the next hour or two.

I’m so excited to have a space to explore writing about films and artists who challenge and inspire us. Thank you for reading this first installment, and I hope you’ll consider supporting this project as it finds its feet.

NEXT WEEK: A look at my favorite film of 2023, and a master of the perfect, satisfying, heart-exploding ending.

NEVER CURSED is a bi-monthly newsletter about movies I love & the people who make them. Over the various world crises, strikes, and “industry contractions” of the past year, it’s been a challenge to remember why filmmaking is personally and politically important to me. I’ve started this column to revisit both old favorites and new wells of inspiration (more on that next week!). I hope you’ll join me.

I want this column to celebrate and reflect filmmaking’s fundamentally collaborative nature – as such, I’m open to any suggestions or requests for newsletter topics!

–

VOL. 1 WATCH & READING LIST

PHANTOM THREAD is available to stream on Netflix & is playing in LA at Braindead Studios on 2/17

REBECCA (1940) is available to buy from Criterion & is playing in LA on 2/16 and 2/18 as a part of American Cinematheque’s Nitrate Film Festival

Phantom Thread Costume Designer Mark Bridges’s Criterion Closet Picks

Natalia Winkelman on our cinematic crybaby era for NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/27/movies/barbie-poor-things-and-petulant-men.html

Michael Newton on the wayward occultist/novelist Charles Williams for LRB: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v38/n17/michael-newton/i-love-you-defiant-witch!

🍄💝