NEVER CURSED VOL 3: Dune Part Two

Wrestling with the power of Denis Villeneuve's would-be anti-colonialist epic

Long before I fell in love with filmmaking, I fell in love with Dune. I spent most of my childhood summers lying on the floor of my grandmother’s house in France, legs pressed to the cool stone, eyes glued to a book. At the start of every summer, my sister and I would go to the local bookstore and stock up on novels in English to bring with us. I’d scan the shelves and grab the fattest books I could find, hoping for stories dense enough to fill the empty weeks stretching out in front of me. When your main search criteria is “long,” you’ll inevitably end up in the sci fi and fantasy section, which is almost exclusively filled by doorstoppers. The most important and challenging of those summer reads for me was Frank Herbert’s Dune. I can still picture it hulking on the shelf, as wide as it was tall.

Dune confounded me: Herbert’s prose was impenetrable, his themes enticingly adult (interstellar corporate intrigue, messainic jihad, witches who invented religions for their own political gain, etc). This was not fantasy à la JK Rowling or CS Lewis, where everything was spelled out for a young audience. The holes and contradictions in Herbert’s world-building that would later madden me as an adult reader were thrilling invitations to invent new, impossible images for myself (how do you ride a giant sandworm, exactly?). I relished the fact that to make it through Dune, you have to forge ahead single-mindedly, acting as both reader and editor as you throw yourself into the text.

It was clear from Dune (2021) that Denis Villeneuve approached adapting Herbert’s text in that same spirit, delighting in the opportunity to bring the source material to life while also understanding the adjustments needed to avoid many of its dramatic pitfalls. He cleaved the book in two and streamlined the story to focus on Paul (Timothée Chalamet) and his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) as they contend with palace intrigue, the contradictions of being “friendly” colonizers, and, eventually, the death of Paul’s father, Duke Leto (Oscar Isaac). Dune: Part Two (2024) picks up almost immediately after Dune leaves off, with Paul and Jessica taking refuge in the desert of Arrakis with Chani (Zendaya), Stilgar (Javier Bardem), and their native Fremen tribe.

The first Dune film begins with Chani’s voiceover describing the occupation of Arrakis by off-planet powers, a narrative frame that efficiently positions the film as an anti-colonialist parable. Dune: Part Two trades in Chani’s opening VO for Princess Irulan’s (Florence Pugh), explaining the betrayal of Leto Atreides by the Baron Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgaard) and Irulan’s father, the Emperor (Christopher Walken). The second film’s framing device presents this as a simple story of filial revenge, rather than an overtly political text with potential real world resonances. This concise, in some ways effective opening is an early indicator of both the second film’s emotional power and it’s missed political potential, something that it’s taken me several viewings to grapple with.

In a recent episode of Unclear and Present Danger, Jamelle Bouie and John Ganz’s podcast about 90’s political thrillers, they discuss the dangers of cinematically effective but politically insidious films like The Birth of a Nation and Triumph of the Will, asking whether films at this scale should be allowed to exist at all, given cinema’s powers of persuasion. I’d like the answer to be yes, if the American film industry was capable of producing epics with a critical political perspective. But with Dune: Part Two, it’s clear that the most we can hope for is awe inspiring craftsmanship masking fuzzy politics.

To be clear, I had a sublime experience watching the film. Dune: Part Two makes full use of cinema’s immersive capabilities, to an almost overwhelming degree. It is thrilling, and moving, and ambitiously inventive in a way that we rarely see now — exactly the type of film I hoped for as a child in love with the world-expanding immersiveness of sci fi and fantasy. But that immersive potential, the thing that makes me love filmmaking so much that I’ve devoted my life to it, is what makes me fear its political misuse — or, in this case, disuse — above all else. While the politics and prose of Herbert’s text tend to be so incomprehensible that they’re rendered largely unthreatening, you can’t help but imagine a version of this narrative streamlined and weaponized under Villeneuve’s masterful hand that could be used as a persuasive, world-shaping anti-colonialist rallying cry. What we get instead with Dune: Part Two is some of the most innovative epic filmmaking of the century in service of a vaguely cautionary narrative that I fear will have American audiences sitting back in easy enjoyment, when we should be leaving disturbed by our own complicity in, and leadership of, modern colonial projects.

Villeneuve is an incredibly effective filmmaker who uses sound as much as image to grip his audience’s attention. The fight sequence that opens the film teaches the audience how to listen — also the first Fremen skill that Paul learns. Though there is little dialogue in this opening sequence, Villeneuve demonstrates to the audience that the desert is not silent. He layers rushing footsteps and quiet breaths to generate tension as Paul and Jessica play cat and (desert) mouse with the Emperor’s soldiers. Only the imperial fighters are truly silent, and this eerie quiet immediately marks them as alien. You can’t help but lean in eagerly to the film’s hushed start, a welcome change from the immediate shock-and-awe teasers that so many contemporary action movies rely on. Then, the pulsing thuds of a thumper break through the silence, and are soon joined by the shockingly loud crashes of Sardukar bodies tumbling from the rock face that they’d ascended in balletic silence only seconds before. There is something overwhelming and elemental about Villeneuve’s command over his cinematic toolbox, using cinema’s greatest asset, point of view, to craft sounds and images that refuse to loosen their grip over your attention. By a few minutes in, it’s almost impossible to think of anything outside of what’s playing out onscreen.

This immersive skill is helped massively by seeing the film in IMAX. Dune: Part Two feels surprisingly intimate compared with other desert epics, in part because of the way that Villeneuve and DP Greig Fraser (who will forever have my heart for his beautiful, sensitive lensing of Jane Campion’s Bright Star) embrace IMAX’s square-ish format. The format allows for the grand sweep of desert vistas to mingle with intimate moments between characters, sometimes in the same frame. Dune: Part Two is at its most arresting in its beautiful wide shots of the desert, often foregrounded by blurred human bodies dwarfed by the elements. Under Fraser’s lens, the desert remains unknowable, always in flux, mirroring Paul’s discovery of its secrets – yellow under a high noon sun in one scene, silvery lavender under alien moons in the next. In these shots, you can feel Herbert’s passion for ecology leaping from the page to the screen, an uncanny act of visual adaptation.

Chani and Paul’s love story begins in one of these shots, as the two of them walk out in synchronized choreography over an ocean of pale blue sand. I was reminded that, before being the king of elevated, big budget action films like The Batman and Rogue One, Greig Fraser shot one of my favorite romantic dramas, Jane Campion’s Bright Star. (If you haven’t seen it, please watch it – it’s only through Much Discipline that it’s taken three whole installments of this column to bring it up; a friend once said to me that Bright Star captured the feeling of realizing that you’re falling in love better than any other film, and I’m tempted to agree.) There is little space for that kind of romantic reflection in Dune 2, and subsequently a lot of the romance between Paul and Chani is communicated in shorthand that can feel unearned. I fervently hope that Fraser makes time in his schedule to shoot something soon that will give him time and space to explore human emotion in a more grounded setting. Based on the amount of emotion that he’s able to imbue the few quick shots we get of Paul and Chani learning to walk together, he’s now at a place in his craft where he could truly break our hearts open, if given the right material.

That being said, Chani’s character is a huge improvement in Dune 2 compared to the source material. In Villeneuve & Jon Spaiths’s hands, Chani is a formidable skeptic, resisting Jessica’s religious propaganda. In the books, Chani is largely a follower, blinded by love and faith. In the films, there are much more (unspoken) similarities between Jessica and Chani, both defiant concubines humming with lives of their own outside of their relationships with “important” aristocratic men. To Zendaya’s Chani, Paul is merely a boy to be doubted, teased, and eventually loved, not an off-world messiah pre-destined for greatness. But their romance is constantly mediated by the desert conflict, whether visually in two shots of them looking out at the sand, or through the way that their love theme slides between delicate romantic yearning in one moment and bombastic rebel war anthem in the next. Throughout the film, she fights against their love story being subsumed by the violent circumstances they live in, though the tension that Zendaya conveys in her physical performance hints that the weight of her people’s future is impossible to forget even for a second.

These anthemic battle sequences, especially in the first half, are elementally, viscerally cinematic. They’re cleanly blocked and deliciously legible compared to the overcomplicated, overstuffed sequences in so many comparable elevated epics (sorry, Tenet). As I’m writing about Dune: Part Two, it is so tempting to slide into the style of apolitical, formalist analysis that I was trained in (in the school of the late, great David Bordwell). Villeneuve and Fraser prove themselves to be perfect collaborators in the framing and editing of the harvester fight sequence: playing with trademark obfuscated foreground elements (particularly in the shot of blurry Fremen fighters crawling desperately to escape the gnashing harvester’s teeth, sharp and menacing in the background); in their truly innovative, seamless integration of CGI (I gasped at how the camera struggles to keep the little CGI desert mouse – “Muad’dib” – in focus as it darts around at the beginning of the sequence, a subtle, ingenious choice that gives the illusion that the cameraman is attempting to follow a real object); and in the way the scene uses shadows cast by the high desert sun to establish clear stakes – dash across the bright sand to safety, or die. But this sequence’s visceral depiction of ground-to-air fighting between two factions with dramatically different resources is what eventually pulled me out of the film for the next 20 minutes. The same skill that rendered it so immersive made it almost unbearable to watch, so undeniable were its parallels to the ongoing conflict in Gaza. As the cast and crew toured the world promoting the film, countless thousands are dead in the very real desert, and a devastating famine is setting in due to American bombs, pathetic American gestures towards aid and reconciliation, and passive indifference that is coming to define the American public’s relationship to its government’s foreign policy.

Throughout the first half of the film, I found myself constantly distracted by these parallels, especially in Paul’s premonitions of the famine and death that would be caused by this war. The message of Paul’s role in these visions is somewhat muddled -- it is Paul’s leadership that will bring about famine and bloodshed, but in these subjective flashes it is his mother who leads them towards that fate, an Oedipal transferrence of blame that somewhat defangs Paul’s late turn from hero to anti-hero at the end of the film. But Jessica’s turn from protective mother to jihadist propagandist (a word omnipresent in the books but selectively excised from the film) is a welcome sharpening of Herbert’s books’ warnings against the destructive potential of soft power.

What then, does the film make of its own soft cultural power? The silence surrounding its release is uncanny, but to be expected. Dune: Part Two exemplifies the heights and deficits of American studio filmmaking. Villeneuve wields his formidable budget and highly trained, creative crew to generate moments of spectacle and emotion that are profoundly moving in the moment, but you get the sense that the same immense resources that allowed the production to shoot in real world locations and build gorgeous practical sets are also what make any real political statement beyond “colonizer bad” out of the question. This is a beast of a film and a bear of a marketing campaign, and I can’t imagine an American studio risking a boycott of an investment this size. That’s no excuse, especially for the silence of the American press. When doing research for this piece, I couldn’t find a single mainstream publication whose primary review explored the political and cultural context that this film was released in. It is no surprise to me that Warner Bros. would place an embargo on any of its cast and crew discussing the real world parallels of Dune: Part Two’s desert warfare — particularly jarring in the case of Florence Pugh who starred in Park Chan-wook’s excellent miniseries adaptation of The Little Drummer Girl, about an ambivalent actress caught up in the Israel-Palestine conflict of the 1970s — but it’s a profound disappointment that this has hamstringed the press’s response as well.

Much has been written about Villeneuve’s deliberate shift away from the book’s clear Arabic and Islamic influences, but the Middle Eastern landscapes of Dune ultimately betray the book’s source of inspiration. Throughout Villeneuve’s career, he’s shown a clear fascination with the relationship between the body and the landscape, a sort of cinematic Barbara Hepworth, parsing the sublime emotions that are conjured up when confronted with nature’s power (“desert power!”). There are times when this relationship has clear emotional and political stakes, like in the shots of Chani foregrounded in soft focus as she looks out on her desert home. But it’s unclear what Paul –and therefore the viewer--’s relationship to the desert landscape is. A home of sorts, and one he’s eager to claim as his own, but, ultimately, Arrakis’s resources (human and natural) are a bargaining chip in his personal vendetta against his father’s killers. The framing VO at the start of the film means that even after Paul appears to be sincerely radicalized to the Fremen cause, one can’t help but think this is all an excuse to weaponize the struggle of an entire people for an aristocratic revenge mission. Herbert’s book made it clear what the Fremen stood to lose personally and culturally in this war, but Villeneuve, in his desire for a clean cinematic narrative, doesn’t allow for enough cultural or emotional detail to encourage the audience to understand the Fremen cause on a personal level.

Because of the vagueness of the film’s relationship to its clear Islamic and Arabic influences, all that is really left to parse in the Fremen’s minimalist, brutalist world is material, and the materials of the desert cannot lie. The fact that the film’s first half feels impossible to divorce from the real world is in large part due to production designer Patrice Vermette’s grounded, textured sets that reveal much through omission. Scenes on Arrakis feel less like slick, futurist sci fi than a sort of biological fiction or eco-futurism. The props in particular are carefully crafted from real materials to answer the needs of life in the desert (personal highlights being Jessica’s woven, basket-like carriage that she uses to ride a giant worm into the South and the ND filters that slip into place over weapon sights throughout the movie -- which I like to think were born out of the filmmakers’ experience shooting the first Dune in a bright, unforgiving desert). But because not much has been invented to replace Herbert’s lengthy, Orientalist, & at times blatantly racist descriptions of sietches full of “Fremen stench,” the scenes in the Fremen’s territory can feel visually pared down to the point of reduction, rather than distillation. (This reductive tendency can be felt in some of the Fremen characters as well: Stilgar transforms from an enigmatic, formidable leader in Dune to simple comedic relief in Dune 2 with little personal motivation beyond cheering Paul on.) If I’m being generous, this visual tendency towards empty brutalism was made to reflect a society that prizes minimalism and resource conservation. But I’d hoped that the ornate carvings in Arakeen in Dune were promises of a richer, more fully realized Fremen civilization in Dune 2.

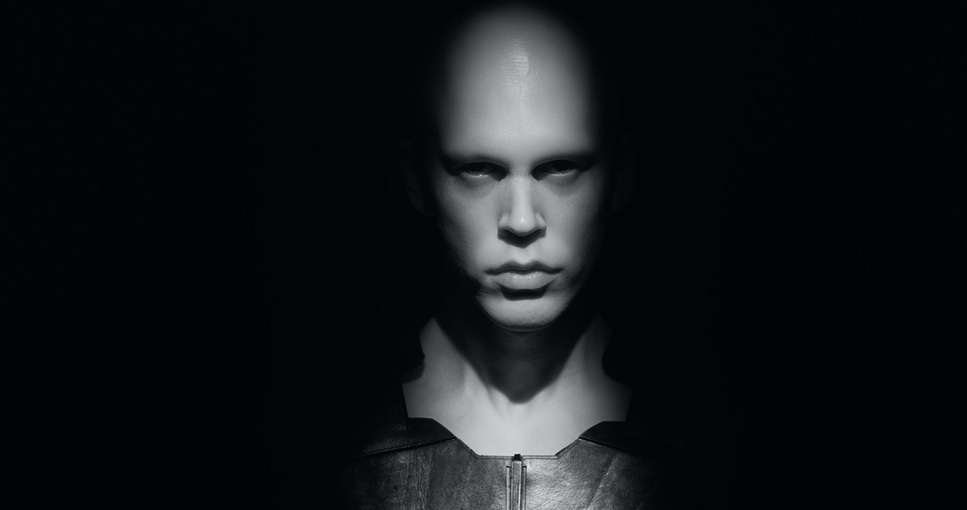

It is a strange relief, then, when the film leaves Arrakis at the midpoint to set up Feyd Rautha (Austin Butler) on the Harkonnen planet of Giedi Prime. There, the familiar visual language of fascism is much easier to parse than the fraught desert fighting of the film’s first half. The black and white infrared arena sequence is undeniably one of the most inventive and beautifully executed sequences I’ve seen in a science fiction film in years. Every department is operating at full force to invent a completely new visual language, from the innovative cinematography to the gorgeous hair and make-up work on Austin Butler and Lea Seydoux, to the queasily wet CGI fireworks squelching overhead. Villeneuve’s talent for immersive, grounded world-building is exemplified in a set of deceptively simple shots tracking the Bene Gesserits and the Baron Harkonnen as they pass from indoors into the infrared sun, their costumes and skin gradually bleaching as they walk into uncanny B&W. By contrast, the Harkonnen interiors are styled like a 2000s Tom Ford for Gucci commercial, deep blue-blacks and slick bondage-inspired costumes coldly lit from overhead. The seduction of Feyd Rautha is such a complete visual and auditory mindfuck that I almost cheered when the final twist is revealed – not only had Lady Fennering (Seydoux) been sent to seduce the soon-to-be-Baron, but she was testing his mettle with the iconic gom jabbar. Austin Butler is sublime in these scenes, acutely aware of how to use his face, glowering from under his brow and gritting his teeth to mold his skull into an alien death mask.

After the high point of the Harkonnen sequences, the cut aways to the Emperor and Princess Irulan feel almost extraneous to the plot. It’s fitting that the Emperor and Irulan’s scenes were filmed at the Carlo Scarpa-designed Brion Sanctuary complex – initially commissioned as a tomb for a powerful Italian industrialist. From the inside of the Brion tomb, you can see out across the surrounding countryside, but any occupants are cunningly hidden by an angled wall from anyone looking in from the outside. The scenes between Irulan and her declining father are all about this interplay of observation and obfuscation, consolidating power inside while keeping a keen eye on the maneuverings outside the castle gates.

Scarpa’s influence can be felt throughout Patrice Vermette’s textured sets for Dune and Dune: Part Two. The midcentury Italian designer’s work uses modern techniques and materials to produce structures that feel somehow layered with ancient histories. In Scarpa’s buildings and Vermette’s sets, you are always aware of moving towards the edge; the end of one material or structure and the beginning of another. Paul’s story in Dune: Part Two is similarly about resisting the draw of a terrible edge, of remaining small in a landscape and a time that you will one day dominate.

Dune: Part Two, like many of my favorite books and movies, is about the time between the end of one thing, and the beginning of another. In the introduction of his novel The Magic Mountain, about the last days before the cataclysm of World War I, Thomas Mann wrote:

“the extraordinary pastness of our story results from its having taken place before a certain turning point, on the far side of a rift that has cut deeply through our lives and consciousness…[And] is not the pastness of a story that much more profound, more complete, more like a fairy tale, the tighter it fits up against the "before"?”

Villeneuve’s film is similarly positioned on the precipice of a cataclysmic turning point. At the end of the film, Paul finally embraces his many names and singular “terrible purpose,” severing ties to the old Empire, and cleanly marking the start of a new era. Villeneuve and his co-writer Spaihts are much more explicit than Herbert’s first book in depicting this climax as the rise of a dangerous messiah rather than the victory of a morally just hero. Paul tells Jessica that he must act like their Harkonnen relatives in order to rise to power. Villeneuve uses shifts in costuming and score to mark Paul’s turn from Atreides pup-in-training to brutal Harkonnen-Atreides leader: Paul strides into the Fremen council meeting in a villainous black cloak as Zimmer’s score churns with echoes of the groaning electric guitar from Feyd Rautha’s arena battle theme. And instead of ending on a hero shot of Paul after killing Feyd Rautha and securing the Empire by arranging a marriage with Princess Irulan, the film ends on Chani, alone and betrayed by her colonizing lover.

By bookending Dune and Dune: Part Two with Chani’s POV, Villeneuve signals his own distrust of Paul and a belief in the anti-colonialist Fremen’s perspective. Dune: Part Two is a reminder (or cautionary tale) of the emotional and political power of cinema when its being crafted by filmmakers at the height of their powers. Villeneuve and his collaborators appear to have solidified the murky politics & message of Herbert’s first Dune novel into what structurally seems like a clear, persuasive anti-colonialist position & cautionary tale against charismatic leaders. But there is something hypocritical in American audiences embracing this message and enjoying this film when it is American bombs currently being dropped across the real desert, destroying lives and cultures far more rich and nuanced than their reductive on-screen analogues. We are so used to watching films born out of narratives of scrappy, underdog American exceptionalism that I worry that audiences will walk out of the theater satisfied, rather than horrified, like finance bros who walked out of Wolf of Wall Street giving each other high fives. As Joshua Pearson wrote about the first Dune, “While the seductive fascist aesthetic is right up on the surface, inescapable, the critical and estranging elements have proved all too easy to miss.” We are invited to see ourselves in Paul, the off-world savior, but his destined moral turn comes too late for most audience members to really take in the implications. Like Paul, I have a creeping sense of our historical “terrible purpose” if we continue to passively accept our own self-valorizing narrative as being true. Without a clear call to action from the film’s cast and crew, I can only hope audiences leave the theater holding Chani’s skepticism of the film’s fatalistic message.

—

FURTHER READING

Costume Designer Jacqueline West on the Bene Gesserit’s costumes -- https://www.vogue.com/article/dune-part-two-costumes-jacqueline-west-interview

Production Designer Patrice Vermette on Scarpa and the Brion Sanctuary -- https://www.indiewire.com/features/craft/dune-2-locations-brion-sanctuary-kaitain-veneto-italy-1234961395/

Fab interview with Cinematographer Greig Fraser on designing the many looks of DP2 -- https://www.vulture.com/article/dune-part-2-scenes-sandworm-ride-feyd-rautha-fight.html

Joshua Pearson on the politics of Dune -- https://tribunemag.co.uk/2021/10/dune-denis-villeneuve-frank-herbert-science-fiction-book-film

& his very interesting academic article on Paul as a symbol of capitalist self-investment -- https://muse.jhu.edu/article/723518

Chris Dite on the fraught relationship between the left, Dune, and Herbert’s own libertarian conservatism -- https://jacobin.com/2021/08/dune-herbert-science-fiction-conservatism

Manvir Singh on the construction of Dune’s alien languages - https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/dune-and-the-delicate-art-of-making-fictional-languages