I don't believe in heroic sculpture – I want to get the human relationship right.

- Barbara Hepworth

Leaving the theater after seeing La Chimera, I felt like turned-over earth, the darkest, stillest parts of me freshly exposed to the elements. Rohrwacher’s films always stir this feeling in me – like I’ve had a brush with something sublime and unnamable, buried deeper than I usually dare to look.

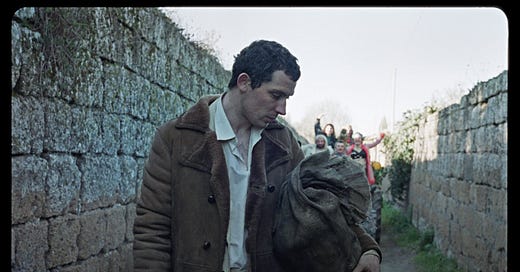

We meet Arthur (Josh O’Connor) similarly between worlds. His body is asleep on a train but his mind is elsewhere, in the sun with an agitated young woman in a crocheted dress. His dream is interrupted by an insistent but genial ticket taker, and Alice Rohrwacher’s latest film, La Chimera, takes tentative root in the 1980’s. From the start, Arthur’s mind is with old things, telling the group of young Italian girls in his compartment that they look like Etruscan paintings. We size him up with the girls, like Joan Fontaine giving Cary Grant a once-over across the train compartment in the opening of Hitchcock’s Suspicion. Is he hitting on them? Insulting them? Flirtatious? Dangerous? His flaring temper doesn’t give us an easy answer. Meanwhile, his friend Pirro (Vincenzo Nemolato) waits for Arthur in a crowded station. Next to him, children look at Etruscan frescoes through souvenir viewfinders. “What can you see?” Pirro asks. “People!” they reply.

In this rumbling first scene, Rohrwacher introduces her primary subject – both “People!” and person – and teases many of the significant themes and formal choices threaded throughout the film to come. Importantly, we meet our protagonist, Arthur, at the same time as the collective, establishing hero and chorus on equal narrative footing. The scene is short but thematically rich: Rohrwacher introduces dreams and omens, Arthur’s uncanny connection to the past, and capitalism’s intrusive relationship to both the ancient and the arcane. Cinematographer Hélène Louvart and editor Nelly Quettier skillfully layer multiple film formats throughout the sequence, beginning the film’s archaeological exploration of cinematic texture. Rohrwacher is often praised by critics for her “whimsy,” perhaps because of her dry sense of humor, but as this opening shows, Rohrwacher’s films are anything but capricious. Her work is deeply rooted in an instinctive but carefully considered understanding of narrative structure, film form, and cinematic history.

From Sonnets to Orpheus - Part 1 Sonnet 10

You’ve never been away from me, antique

sarcophagi, but I greet you…

We quickly get the outlines of their immediate backstory: Arthur is an English archaeologist returning from a stint in prison related to his & Pirro’s exploits in a gang of tombaroli – part of the wave of Italian grave robbers who raided Etruscan tombs in the 1980s, fueling a black market whose profits, according to an interview with Rohrwacher, rivaled that of the drug trade. Arthur resists his old friends’ invitation for a drink, instead visiting Flora (Isabella Rosselini), the aging mother of his lost love, Beniamina (Yile Yara Vianello, who starred in Rohrwacher’s first feature, Corpo Celeste1). Eavesdropping as they talk is Flora’s latest servant-slash-music-student, Italia (played by Brazilian Carol Duarte), as tone deaf as she is horrible at chores.

Flora’s home crumbles around the trio, a nostalgic tomb waiting for her daughter’s unlikely return. Arthur’s own ramshackle hideout isn’t faring much better, dusty artifacts piled compulsively into every leaking corner like seashells in a beachside B&B. Arthur’s world is wobbily constructed from discarded things and forgotten people which, as Alice Rohrwacher’s sister Alba says in a brief (but wonderful) cameo later in the movie, “one day the rust will eat away.”

Arthur’s comrades wave off his coy attempts to leave the group, and the gang is soon raiding the Italian countryside, guided by Arthur’s supernatural ability to locate tombs via a slender dowsing branch. Surrounding Arthur with his fellow tombaroli, Rohrwacher offers a compelling, more truthful alternative to our default narrative of the swashbuckling adventurer: only with the support of the collective can we survive a hero’s journey. The tombaroli form a Greek chorus to score Arthur’s Orphic story, their cheers transforming his occult connection from a burden into a gift.

As I watched Arthur and his friends lift ceramic treasures out of the dirt and wrap them in plastic bags crinkled with reuse, I thought of my mother, a potter. She sends her work to me encased in layers of recycled bubble wrap and newspaper — it’s always a project to excavate a new piece. Using the bowls and cups that she’s made feels like a dialogue between us: shaped by her hands, worn by my use. During the film I found myself thinking for the first time that, after she and I are both gone, her pots may find their way into the earth, peppered with her fingerprints, a piece of her preserved. I can’t remember the last time a film revealed such a deeply-buried hope, articulating an existential desire that I hadn’t let myself look at directly. Like Arthur, I needed the company of a chorus (the filmmakers, my fellow audience members), to dig up something buried that deep.

From Sonnets to Orpheus - Part 1 Sonnet 6

Is he of this world? No, he gets

his large nature from both realms. To know

How best to curve the willow’s boughs

you have to have been through its roots.

Arthur’s not entirely of this world, but he’s not an angelic creature either, more reminiscent of Jack Nicholson’s slouching American drifter in Antonioni’s The Passenger than Wim Wenders’ dislocated angels in Wings of Desire. He’s a man who holds grudges, starts fights, takes himself too seriously and, in turn, makes himself ridiculous. He’s also becoming something of a local legend, a folk hero immortalized in song, and he’s vain enough to not entirely dissuade this nascent mythology.

Rohrwacher said in a conversation with Jeremy O’Harris for Interview that “the figure with whom I identify the most is the tightrope walker, but not the one who walks across like it’s nothing, but one who is hesitating, who is sort of wavering a little bit, and despite almost a few missteps manages to make it across.” Arthur’s ability is similarly hesitant and mercurial, a mystery that Rohrwacher doesn’t over-explain. She allows O’Connor’s performance of this otherworldly gift to remain subtle, externalizing the feeling of him crossing over to the other side through camera movement and sound design.2

Throughout the film, Rohrwacher and her collaborators visually depict Arthur’s crossing over as an inversion, first through a tilting camera movement that flips Arthur in the frame, then in an edit that flickers between Arthur upright and his inverted double, and finally in a grounded, static shot of Arthur standing over his inverted reflection in a muddy pool. He is the tarot deck’s Hanged Man, suspended from a mythic tree with roots in the underworld with no choice but to surrender to the double-edged sword of spiritual receptivity. Any moment of earthly happiness with Italia is interrupted by the compulsive pull of the other world. In a beautiful scene at the film’s midpoint, Italia has been embraced by the gang and seems to be drawing Arthur back to the land of the living. She tentatively lays her head on his shoulder and a smile ghosts across both of their faces for a moment, but Arthur flinches away. His breath halts unsteadily and his body shifts into a predatory hunch. Rohrwacher cuts between Arthur and his inverted double, and by this point in the film we’re well-primed to recognize the treasure hunt that’s coming next.

All of this takes place under the eerie tungsten glow of a hulking power station (during a devastatingly funny and accurate small town dance scene, the MC whoops, “Hooray for the powerplant!”). Rohrwacher’s films are deeply connected to the landscape but realistic about how mankind has ravaged it. Arthur and his comrades unseal tombs that lay still for thousands of years, a vocation that Arthur’s budding romance with Italia will force him to reconsider. Though the film also deals squarely with the human cost of capitalist “progress,” the capitalist death drive is at its most violating in La Chimera when it defies our linear narrative of history: capitalism reaches into the past, clawing the earth with rusting metal teeth, transforming vessels crafted for gift or tribute long before the invention of capital into mercenary objects of transaction.

From Sonnets to Orpheus - Part 1 Sonnet 2

Where’s her death? Do you have time to find

That subject before your song burns up?

Though La Chimera is in part an undeniably funny, knowing, and humane ensemble comedy, at its heart is a profound understanding of grief. Rohrwacher started working on the project while Italy was ravaged by the Covid pandemic. Death presses in on all sides, in the dangerous work of the tombaroli and the changing of the seasons. Both Flora and Arthur are compulsively isolated by their search for Beniamina. Flora wars against the world’s “slow forgetting” of Beniamina, as Isabella Rosselini described her own grief over her parents’ death. She and Arthur both know that no matter how busy you make yourself, grief is always lying in wait: After a vibey montage of successful grave-robbing hijinks (set to an amazing Kraftwerk needle drop), Arthur is napping in the backseat of a moving car when he sees a red thread from Beniamina’s dress unspooling past the window, the other side beckoning him yet again. O’Connor plays these bittersweet visitations beautifully, telling us in a look that Arthur’s callused, cynical relationship to the dead – he’s a grave robber, after all – wars with a reckless flickering of hope that what (or who) is lost can be found again. His subterranean wanderings feel like revisiting a fading memory of someone who’s gone – a desperate fumbling down a dark passage, trying to memorize its details before the light of your candle goes out.

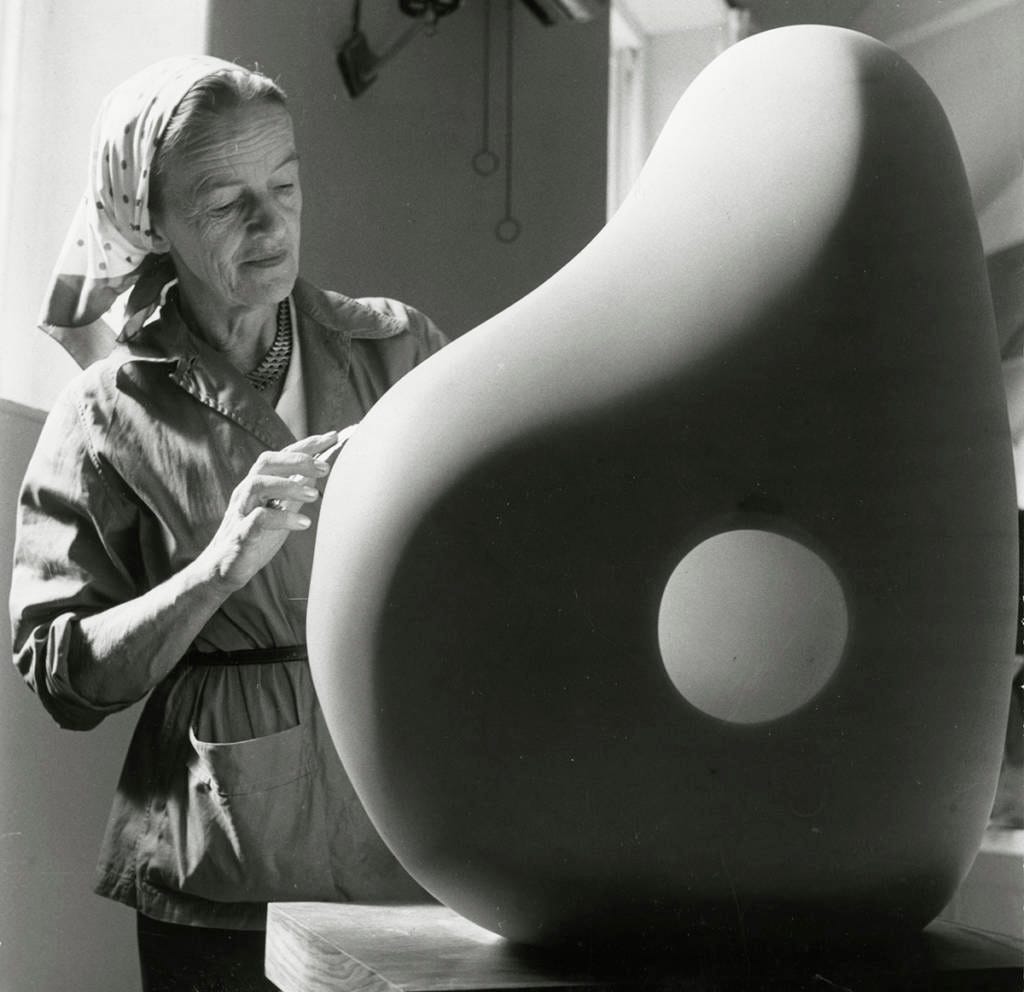

After La Chimera drew to a close, I was reminded of the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, whose pieces similarly deal with the relationship between the individual and the collective, pierced through by an unyielding, unifying void. In the darkened theater, I felt Rohrwacher call into that void, uniting the room via our essential human experience of loss. You don’t watch La Chimera, you encounter it: twisting and unfurling elusively like a living thing, beautiful to observe, until - suddenly - it looks straight at you, naming a long-buried piece of your heart. Pure cinema, pure emotion; something we don’t quite have words for, but can’t deny when we hear its call.

Sonnets to Orpheus - Part 1 Sonnet 17

Deep under all that’s been done,

entangled and ancient,

a hidden source, a root

no one has seen.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. David Young

If you’re familiar with Alice Rohrwacher’s films, you’ll recognize most of the faces crowded into La Chimera – locals that the Italian director has cast across her films which she calls “collective portraits,” forming an ever-expanding troupe of actors and non-actors alike. One of the (many) great joys of watching Rohrwacher’s movies is rediscovering these wonderful performers in adventurously varied roles from film to film.

For example: After Arthur and Italia share a fleeting moment of connection in one of the villa’s crumbling corridors, they bring Flora to the abandoned Riparbella train station. Birdsong gives way to the rasping cicadas of Arthur’s dream, and Rohrwacher subtly cues the audience that Beniamina’s memory is never far from consuming him.