For all the chatter about the return of sex to American movie theaters last year, from Challengers’ athletic throuple-ing to Nosferatu’s supernatural bodice-ripping, what surprised & inspired me most in 2024 was the return of genuine cinematic romance. My three favorite films of the year – La Chimera, Queer, and Babygirl – all explored romance in singular and unexpected ways, from Luca Guadagnino & Daniel Craig’s reinvention of William Bourroughs into the world’s saddest lovelorn clown to Alice Rohrwacher’s textured exploration of love, loss, and the objects we leave behind. And while I’ve written about how seeing Queer and La Chimera in theaters were two landmark moviegoing experiences for me, it was weirdly Halina Reijn’s prickly thriller Babygirl that felt the most comforting to me, an answer to a problem that had been nagging at me all year: What happened to the romantic thriller?

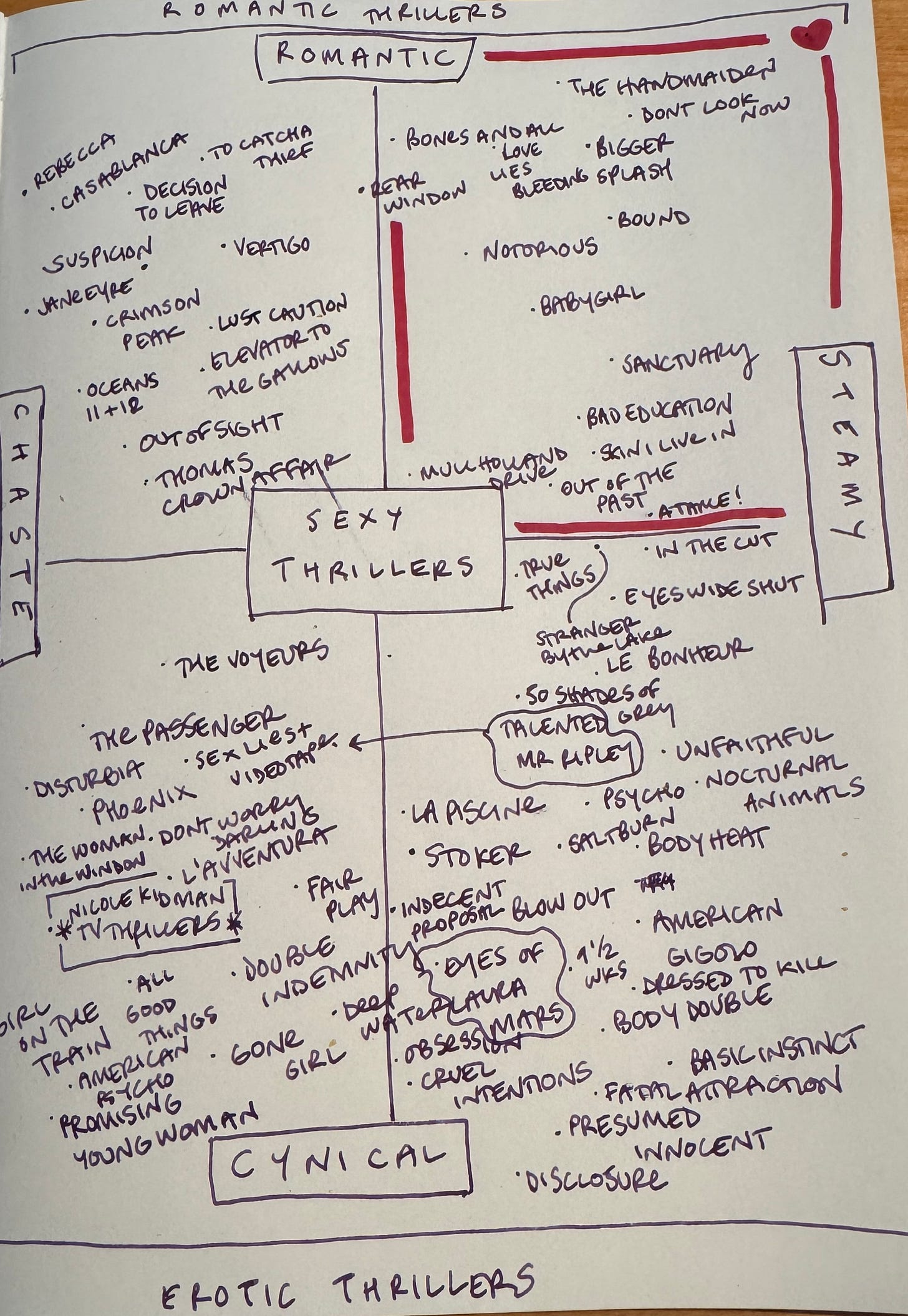

I spent most of 2024 re-watching classic erotic and romantic thrillers, research for a feature I finished this fall. The side result of this months-long binge was this Sexy Thriller Diagram (aka STD1), categorizing thrillers along two axes, Steamy/Chaste & Cynical/Romantic:

Before making The Diagram, I thought of the biggest difference between the romantic and erotic thriller as the amount of skin shown on screen — swooning vs. softcore, “Steamy” vs. “Chaste.” But as my compulsive graph-making continued, I became more and more convinced that the real distinction between the two subgenres lies in the Diagram’s other axis, “Romantic” vs. “Cynical,” i.e. our emotional attitude toward love and lust. While the erotic thriller’s view of love and sex is largely cynical and transactional, the romantic thriller protects an optimistic and at times spiritual view of human connection.

Making this chart brought up questions I haven’t been able to shake: Why are there so many more erotic thrillers than romantic thrillers, especially in the last 30-40 years? By extension, why did the American film industry largely trade in the romantic thriller’s humanist belief in love-as-salvation for the erotic thriller’s fatalistic view of lust-as-transaction? Is one subgenre inherently more conservative than the other?Why, even after trending back toward more chaste, buttoned-up depictions of sex in the ‘00s-10s following the failure of the NC-17 rating (as brilliantly chronicled by Karina Longworth in her Erotic 80s/90s seasons of my favorite podcast, You Must Remember This), have we clung to the cynicism of the ‘80s-90s erotic thriller? Why has Hollywood’s recent trend of remaking and reworking popular adult thrillers emphasized the erotic over the romantic?

We usually think of iconic “romantic” thrillers from the ‘40s like Notorious and Rebecca as more conservative than their skin-baring “erotic” thriller counterparts in the 80s-90s. In some ways they are objectively conservative – glorifying paternalistic May-December romances (Rebecca) or insisting on a previously independent woman’s ultimate need for a male savior (Notorious). On the surface, erotic thrillers seem more liberated in comparison, allowing the viewer to explore desires outside the norms of traditional relationships. But when I looked at these movies more closely, I found the opposite to be true: that the erotic thriller’s cool veneer of libertine cynicism masks a stagnant, fatalistic embrace of capitalist values, while the heart of the romantic thriller promises the possibility of action, reform, and connection.

Erotic thrillers are largely depictions of the inherent dangers of lust, especially to heterosexual marriage and the nuclear family. E.G. :

A man has an affair with a coworker, with disastrous consequences (Presumed Innocent, Disclosure).

A man has an affair with an unstable woman, with disastrous consequences (Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct).

A couple decides to briefly open up their marriage, with disastrous consequences (Indecent Proposal, Consenting Adults).

The affairs in these films are driven by lust and/or financial greed, not love. When women are the cheaters, their affairs are often explicitly financially transactional or involve wealthy older men (Indecent Proposal, 9 ½ Weeks). Collectively, the erotic thrillers of the ‘80s and ‘90s constructed an empty-hearted, capitalist fantasia of transactional relationships, warning against violating sexual and marital norms and of the dangers of female dominance in the workplace.2

The rise of the erotic thriller also feels closely tied to the popularization of the seductive misconception that cynicism equates subversion. While they appear transgressive at first glance, many erotic thrillers are tortured by their own fatalistic conservatism, largely confirming the capitalist, family-values-prizing worlds they inhabit. Ultimately, they encourage conformity and apathy in relation to norms of class, gender, and sexuality.

So it makes sense that, in our current cultural moment when the rights of women and queer people are being rapidly stripped away after decades of progress, Hollywood would return to a familiar, conservative playground. The last couple years have seen an uptick in both original erotic thrillers (Fair Play, Saltburn, Sanctuary, etc.) and TV remakes of erotic thriller films from the genre’s heyday in the 80s & 90s (Presumed Innocent, Obsession, Fatal Attraction). Titan of the genre Adrian Lyne (Fatal Attraction, Indecent Proposal) even returned to directing after 20 years for 2022’s Deep Water, which was both much-watched and much-maligned (a familiar reception for many classics of the genre, which audiences love to watch and critics love to dismiss). But while the industry has trawled every nook and cranny of studio back-catalogs for erotic thrillers to remake, we’ve almost universally ignored the opportunity to update their romantic thriller counterparts (2020’s disastrous Netflix Rebecca remake aside).

Admittedly, I’ve always loved romantic thrillers. The best of them protect a romantic core while being clear-eyed about the injustices and hypocrisies of the world at large, like Hitchcock’s alcoholic, noir-laced thriller Notorious, where Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant play spies engaged in a steamy game of cat-and-mouse in the ruins of a world shattered by WWII. The magic trick of that film – and of the genre in general – is that in spite of its critical eye toward the cruelties of the world at large, it preserves a seed of hope for its damaged heroes: that by allowing love to pierce the heavy veil of world-weary cynicism, we can break our self-destructive cycles and start over. Love (and lust) are what save Bergman and Grant, rather than endanger them. There’s a radical, evergreen call to action concealed at the heart of the romantic thriller: to strive — in spite of real and present danger — to understand and embrace The Other, and understand ourselves better in turn.

Halina Reijn’s Babygirl is the only movie of 2024’s crop of sexy thrillers that heeds this call. It cleverly toes the line between the aesthetics of the erotic and the sentiment of the romantic, creating a truly contemporary thriller in the process. It explores an outré strand of eroticism, sure, but in the service of a story where a woman comes to understand her own needs and desires through an encounter with a lover – without being punished for it.

Romy (Nicole Kidman) is the CEO of a robotics company whose real talent seems to be for gendered performance, whether she’s reciting a corporate quarterly report with husky feminine emotion or putting on an orgasmic show for her husband (Antonio Banderas). In the rare solitary moments when Romy allows her mask to slip, we discover a well of unfulfilled desire roiling just below her Botox-ed surface. After a chance encounter reveals the dominant side of her new intern Samuel (Harris Dickinson), Romy compulsively pursues an affair that risks her professional and personal stability while unearthing long-buried desires.

In a traditional erotic thriller, these desires would spell Romy’s tragic downfall, but Babygirl offers a different shape for a familiar story. After a screening for Babygirl, writer/director Halina Reijn spoke beautifully about the internal tension of being inspired and creatively activated by the erotic thrillers of the ‘80s and ‘90s, but largely being let down with those films’ conservative morals. This paradox resonated with me deeply. Babygirl is a salve for a generation thrilled and punished by the erotic thriller in equal measure.

Babygirl is also excellent, showcasing Nicole Kidman’s rare ability to make you feel like you’re witnessing someone truly exposed and unraveling. There’s no safety net for her character’s actions, and there’s no limit to how vulnerable Nicole is willing to be onscreen. That, to me, is where movies are at their most thrilling. While Romy’s desires are hardly on the extreme end of kink (contrary to the film’s salacious marketing), in her own mind they are transgressive enough that she can’t articulate them to her husband (played by Antonio Banderas, perfect as always). If romance is about true connection with the Other – and discovering a deeper understanding of yourself through their eyes – Babygirl is one of the most romantic movies of the year. It’s a throwback, swooning romance hidden inside the steely corporate casing of the erotic thriller, with a contemporary attitude towards sex and marriage that more than justifies reviving the genre.

Its sex scenes are both unnerving and erotic because of their emotional vulnerability, each one revealing a different facet of Nicole’s character. In this way, Babygirl reminded me of Claire Denis’ brilliant but underwatched Stars at Noon, a steamy political thriller that hides its romantic heart. That film slowly peels back the layers of an initially transactional relationship between Trish and Daniel (Margaret Qualley and Joe Alwyn, giving my favorite performances in both of their careers to date), until Denis briefly, startlingly reveals glimpses of the characters’ authentic, human need for each other. Because it’s Denis, this revelation takes place in a gorgeous, moodily-lit dancefloor. Also because it’s Denis, these characters are slippery and unknowable to the end, making the moments where their masks briefly drop all the more effective. Babygirl shares Stars at Noon’s mercurial elusiveness, leaving you on unsteady ground until the very end.

In the erotic thriller, people who stray outside of marriage put themselves and their families in danger directly caused by their infidelity, and are almost always punished for it. Reijn teases our bourgeois expectations of this type of moralistic punishment throughout Babygirl, charging the last act of the film with heart-pounding energy. In a genre that traditionally demands bloodletting (or at the very least public shaming) for the promiscuous, Reijn ends her film in a way that finds space for both erotic tension and romantic, emotional revelation. Babygirl gives me genuine hope for the erotic thriller, sneakily imbuing it with the best aspects of the genre’s romantic counterpart. Reijn cannily shows us a way to integrate contemporary audiences’ appetite for sex on screen with their desire for complicated, emotionally grounded characters, refusing to conform to prudish modern trends or lazy, conservative genre tropes.

As our culture turns to automation and avatars, we need films like Babygirl, films that thrust us back into our bodies. Reijn’s movie proves that it’s possible to make erotic films that are both bitingly self-aware and emotionally insightful, revealing deeper truths about love and the human experience, as well as the repressive societal rot that threatens our ability to connect. As Merve Emre wrote in her beautiful piece on Sally Rooney’s new (romantic) novel Intermezzo, “No one’s intentions are pure. No one’s actions are consistent. Yet amid this tangle of secrets and lies there is, every so often, a glimmer of mutual understanding—a minor triumph in a world designed to erode all human exchanges and emotions.”

More of that, please.

LETTERBOXD BONUS: Swooning vs. Softcore (a list of some favorite Sexy Thrillers)

*SORRY.

*You could probably trace these anxieties back to the femme fatales of post-war film noirs, also released in a cultural moment where many men were struggling to come to terms with increased female presence in the workplace, and their subsequent financial and sexual independence.